Paintings > Art styles > Academicism

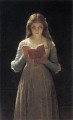

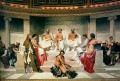

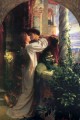

Academicism or Academic art is a style of painting and sculpture produced under the influence of European academies of art. Specifically, academic art is the art and artists influenced by the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, which practiced under the movements of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, and the art that followed these two movements in the attempt to synthesize both of their styles, and which is best reflected by the paintings of William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Thomas Couture, and Hans Makart.

Academicism or Academic art is a style of painting and sculpture produced under the influence of European academies of art. Specifically, academic art is the art and artists influenced by the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, which practiced under the movements of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, and the art that followed these two movements in the attempt to synthesize both of their styles, and which is best reflected by the paintings of William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Thomas Couture, and Hans Makart. The art influenced by academies in general is also called "academic art." In this context as new styles are embraced by academics, the new styles come to be considered academic, thus what was at one time a rebellion against academic art becomes academic art.

Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored. Another criticism by Realists was the "false surface" of paintings—the objects depicted looked smooth, slick, and idealized—showing no real texture. The Realist Théodule Ribot worked against this by experimenting with rough, unfinished textures in his painting.

As modern art and its avant-garde gained more power, academic art was further denigrated, and seen as sentimental, clichéd, conservative, non-innovative, bourgeois, and "styleless". The French referred derisively to the style of academic art as L'art Pompier (pompier means "fireman") alluding to the paintings of Jacques-Louis David (who was held in esteem by the academy) which often depicted soldiers wearing fireman-like helmets. The paintings were called "grandes machines" which were said to have manufactured false emotion through contrivances and tricks.

This denigration of academic art reached its peak through the writings of art critic Clement Greenberg who stated that all academic art is "kitsch". References to academic art were gradually removed from histories of art and textbooks by modernists, who justified doing this in the name of cultural revolution[citation needed]. For most of the 20th century, academic art was completely obscured, only brought up rarely, and when brought up, done so for the purpose of ridiculing it and the bourgeois society which supported it, laying a groundwork for the importance of modernism.

Other artists, such as the Symbolist painters and some of the Surrealists, were kinder to the tradition[citation needed]. As painters who sought to bring imaginary vistas to life, these artists were more willing to learn from a strongly representational tradition. Once the tradition had come to be looked on as old-fashioned, the allegorical nudes and theatrically posed figures struck some viewers as bizarre and dreamlike.

With the goals of Postmodernism in giving a fuller, more sociological and pluralistic account of history, academic art has been brought back into history books and discussion. Nevertheless, since the early 1990s, academic art has experienced a limited resurgence through the Classical Realist atelier movement. Still, the art is gaining a broader appreciation by the public at large, and whereas academic paintings once would only fetch a few hundreds of dollars in auctions, some now fetch millions.

Source: Wikipedia

-

$AU 233.42 ~ 841.50

$AU 233.42 ~ 841.50 -

$AU 255.20 ~ 2,224.76

$AU 255.20 ~ 2,224.76 -

$AU 261.11 ~ 3,094.50

$AU 261.11 ~ 3,094.50 -

$AU 229.31 ~ 845.16

$AU 229.31 ~ 845.16 -

$AU 232.60 ~ 839.65

$AU 232.60 ~ 839.65 -

$AU 252.24 ~ 28,830.55

$AU 252.24 ~ 28,830.55 -

$AU 246.78 ~ 959.77

$AU 246.78 ~ 959.77 -

$AU 281.17 ~ 2,475.02

$AU 281.17 ~ 2,475.02 -

$AU 278.27 ~ 1,668.61

$AU 278.27 ~ 1,668.61 -

$AU 276.76 ~ 1,245.10

$AU 276.76 ~ 1,245.10 -

$AU 264.77 ~ 1,100.94

$AU 264.77 ~ 1,100.94 -

$AU 277.30 ~ 6,019.67

$AU 277.30 ~ 6,019.67 -

$AU 252.50 ~ 2,293.46

$AU 252.50 ~ 2,293.46 -

$AU 258.23 ~ 1,061.17

$AU 258.23 ~ 1,061.17 -

$AU 260.76 ~ 2,188.45

$AU 260.76 ~ 2,188.45 -

$AU 282.37 ~ 5,984.41

$AU 282.37 ~ 5,984.41 -

$AU 281.99 ~ 4,922.77

$AU 281.99 ~ 4,922.77 -

$AU 282.83 ~ 1,156.60

$AU 282.83 ~ 1,156.60 -

$AU 259.90 ~ 953.53

$AU 259.90 ~ 953.53 -

$AU 227.81 ~ 669.14

$AU 227.81 ~ 669.14 -

$AU 227.81 ~ 669.14

$AU 227.81 ~ 669.14 -

$AU 280.28 ~ 11,687.60

$AU 280.28 ~ 11,687.60 -

$AU 278.10 ~ 1,114.57

$AU 278.10 ~ 1,114.57 -

$AU 274.49 ~ 9,480.12

$AU 274.49 ~ 9,480.12 -

$AU 279.50 ~ 1,127.20

$AU 279.50 ~ 1,127.20 -

$AU 271.58 ~ 2,157.17

$AU 271.58 ~ 2,157.17 -

$AU 268.58 ~ 1,648.24

$AU 268.58 ~ 1,648.24 -

$AU 278.58 ~ 1,118.94

$AU 278.58 ~ 1,118.94 -

$AU 279.50 ~ 1,127.20

$AU 279.50 ~ 1,127.20 -

$AU 193.68 ~ 1,044.48

$AU 193.68 ~ 1,044.48